Understanding how datasets are represented in PyLiPD#

PyLiPD is based upon rdflib, a Python package for working with RDF. This begs the question: what is RDF? and why should I care?

Let’s start with the second question. For most of the functionalities present in PyLiPD, you shouldn’t have to care. After all, this is why PyLiPD was created in the first place: to make working with these datasets easier. Therefore, for 90% of your work, you shouldn’t have to care. However, if your work involves generating new compilations of record or you need to create new properties in a LiPD file for future queries, then you need to know a little about how PyLiPD represent the data.

TL;DR: the LiDP structure was expanded into an ontology. One of the languages to write ontologies is RDF. SPARQL is the query language for RDF. Therefore, you can access all the information represented in LiPD files using SPARQL.

Read on to learn more about all these terms:

What is an Ontology?#

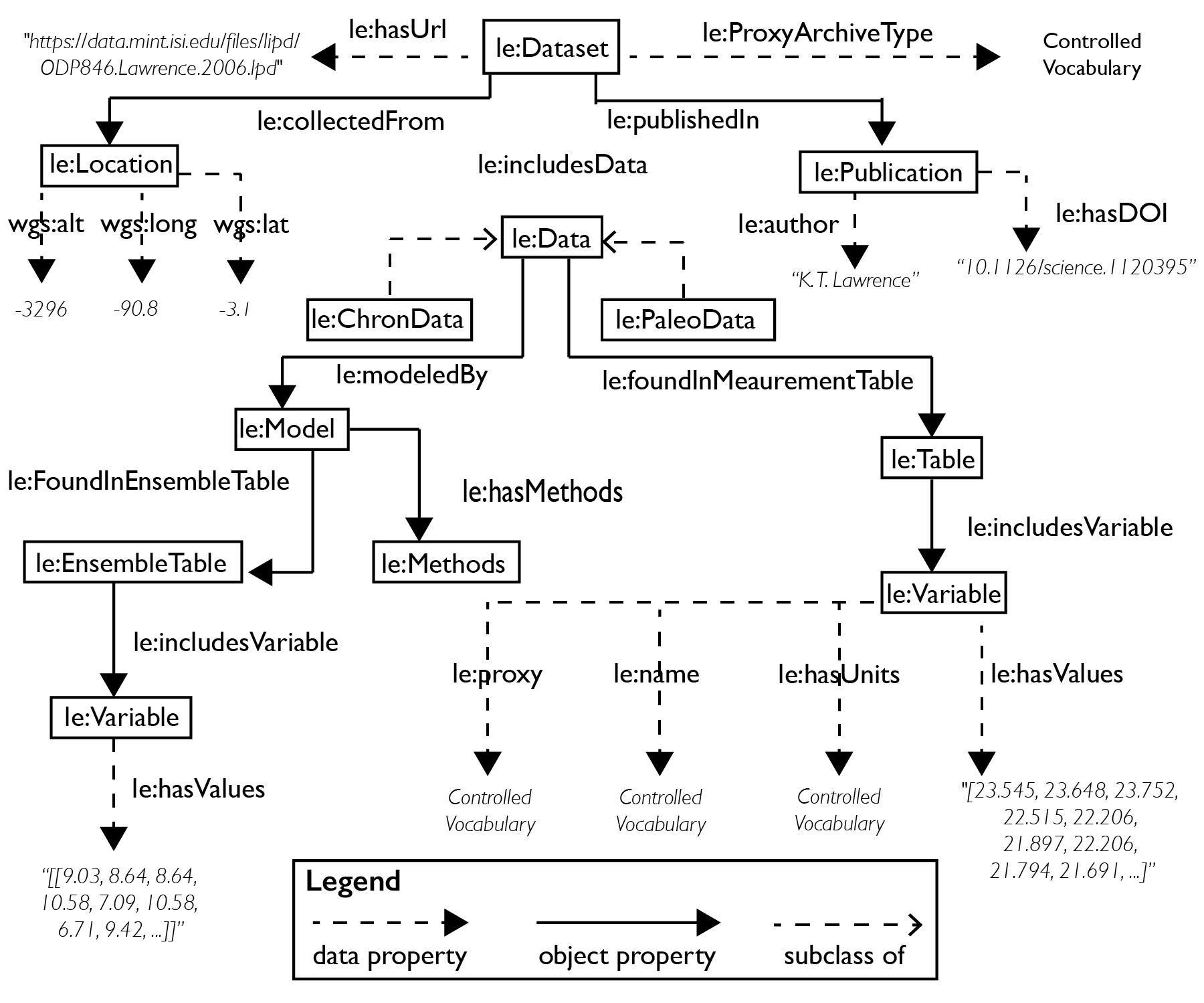

An ontology is a model of (a relevant part of) the world. In our case, the relevant part of the world is a paleoclimate dataset. The ontology lists the types of objects , called classes (e.g., Dataset, Publication, Variable), the relationship that connects them (e.g., Dataset publishedIn Publication), and constraints on the ways that classes and relationships can be combined. A snapshop of the ontology derived from the LiPD format is shown below:

The full ontology is available here. It should help you construct custom queries using the SPAQRL language.

The ontology serves as a map onto which we can load the structured information about paleoclimate data. You can think of the ontology as the equivalent of a database schema. Since we store knowledge, we use the word “knowledge base” instead of database to refer to the organized collection of this information. In essence, when laoding LiPD files, PyLIPD creates a local and ephemeral knowledge base on your computer that you can manipulate to extract relevant information for your scientific work. You will also hear the word knowledge graph to refer to the storing of that information. For all intents and purposes, in PyLiPD, these two words can be interchanged. However, it is often easier to think about the knowledge representation as a directed graph in which the nodes represent the classes and the edges (the connections between the nodes) the relationships among these classes; therefore we strongly encourage you to think about the datasets you are working with as graphs.

If you look at the legend on the Figure above, notice that the relationships are called properties. There are two types of properties: object properties, which relate two classes in the ontology, and data properties, which relate a class with a special call that has been pre-defined, such as “string”, “float”, “integer”. You can think of these data properties as the leaves in the graph.

What is RDF?#

RDF (Resource Description Framework) is a simple language to describe facts about the objects (represented as universal resource identifiers, URIs) and their relationships (constraints need to be expressed in a much richer language such as the Web Ontology Language, OWL). RDF uses triplets to express these facts: a subject, a predicate and an object. Subjects and objects are classes while the predicate represent the property.

For instance, let’s have a look at the following statement:

PREFIX le:<http://linked.earth/ontology#>

le:MD98_2181.Stott.2007 rdf:type le:Dataset

le:MD98_2181.Stott.2007 le:name MD98_2181.Stott.2007

The first line defines a prefix. Remember that in RDF objects are represented as URIs (an example of which are URLs). So this statement essentially says that when we use le later on, we really mean http://linked.earth/ontology# as the prefix to the URI. le is called a namespace.

Let’s move on to the next statement, which is our first RDF triplet. In this case, the subject is le:MD98_2181.Stott.2007 (remember that it essentially is the equivalent of http://linked.earth/ontology#MD98_2181.Stott.2007), rdf:type is the subject and le:Dataset is the object. In English, this can be read as “MD98-2181.Stott.2007 is a dataset”.

Our last statement is another RDF triplet. In this case, the subject is le:MD98_2181.Stott.2007, the predicate is le:name and the object is MD98_2181.Stott.2007. This can be confusing at first, right? Well, remember that le:MD98_2181.Stott.2007 represents a dataset object which can have a lot of predicates (properties) associated with it. One of such properties is its name, which is a simple string. Therefore, le:name is an example of a data property.

Why use ontologies and RDF? This allows us to link our data to the web, which uses this representation to store knowledge. Our ontology doesn’t have many linkages so far. One notable exception is geography, where we reuse the wgs84 ontology, which you will see loaded many times in notebook examples.

Did you know that knowledge bases/graphs power many features you use everyday while surfing the web? Spend some time to research the Google knowledge graph. One of its uses is to create the info boxes that you get from Google searches. Pretty much every large tech company will use a knowledge graph for various applications.

What is SPARQL?#

SPARQL (pronounced “sparkle”) is the query language for RDF. Let’s say I want to return all the names of the datasets stored in the PyLiPD LiPD knowledge base, then I can use the following query:

PREFIX le:<http://linked.earth/ontology#>

SELECT ?dsname WHERE{

?ds a le:Dataset

?ds le:name ?dsname}

This structure should look somewhat familiar. First, we define our namespace le. The querying starts on the next line. We want to SELECT the names of the datasets (represented by the variable ?dsname) that follows some constraints in the WHERE statement. Note that variable names in SPARQL are preceded by question marks. The next two lines should look very familiar. We first created a variable ?ds to store all le:Dataset. Note the a stands for ref:type. Then we look for all the names associated with each ?ds.

If this may sound confusing, don’t worry! You’ll get plenty of practice in our more advanced tutorials (Advanced Querying).